Coming into the BBC from New Zealand television in 1973, I quickly realised that my training and experience as a TV producer / director there did not fit well into the quasi civil service BBC job hierarchy, so at the time I had no choice but to settle for the assistant producer “rank” when I was hired to work as a network director (transmission controller) at the TV Centre in London, on a series of short-term contracts. The job was a means to an end; I wanted get back to making programmes as soon as possible.

Coming into the BBC from New Zealand television in 1973, I quickly realised that my training and experience as a TV producer / director there did not fit well into the quasi civil service BBC job hierarchy, so at the time I had no choice but to settle for the assistant producer “rank” when I was hired to work as a network director (transmission controller) at the TV Centre in London, on a series of short-term contracts. The job was a means to an end; I wanted get back to making programmes as soon as possible.

In those days BBC Television didn’t normally hire programme directors. Instead they called them assistant producers. A fairly meaningless title really, as almost everyone on a production assists a producer. Also an insulting title, especially on live programmes, where the split second decisions of the programme director translate instantaneously into actions which dictate what the viewer sees and hears, independently of a producer.

In a more flexible organisation being a contractor might have enabled me to compete for staff jobs on the same salary scale, but Auntie always protected her own, so in practice, because my job in presentation at the Television Centre was not a “staff” position, I was barred from applying for secondments elsewhere in the BBC, the normal pathway to substantive staff jobs. I did apply for directing jobs, and often got shortlisted, but they nearly aways went to staffers on secondment. Such was Auntie’s way.

There were exceptions to this discriminatory practice, and one of them was jobs outside London, still universally and condescendingly known as “the English regions“. Southampton, Plymouth, Norwich, Bristol, Birmingham, Manchester, Newcastle, Leeds – regions created to fit transmitter locations, rather than for any cultural reasons.There was also a tradition that working in a region was seen as a temporary but useful career move, especially in journalism. Many a now-famous broadcast journalist did their time and learned their trade in a BBC English regional TV or local radio station.

Also, having failed earlier to crack the no-union-ticket-no-job catch 22 which prevented me from getting a job at Scottish Television, thanks to the ACTT closed shop, the idea of a BBC regional job had some appeal, even though not what I had hoped for. So, for better or worse I ended up in 1976 accepting a post as an assistant producer at BBC South, based in Southampton.

The first surprise when I went to Southampton for the interview was that if I got the job I would be working out of the former HQ of the Cunard Shipping Line, who had taken over the grandiose South Western Hotel when they moved their UK base from Liverpool in 1965. This was the only BBC station complete with disused railway platforms, now in use for car parking, with overgrown track beds inhabited by rabbits and butterflies. At first sight it seemed oddly familiar. I realised that this was the very station my wife and I had passed through on the boat train to Southampton docks in 1967, to board SS Northern Star on our way to New Zealand. It now housed the BBC studio and offices, along with Radio Solent, but still retained the atmosphere of better days, with a splendid Victorian marble entrance hall, grand staircase and mahogany doors. It’s now been converted into luxury flats.

The first surprise when I went to Southampton for the interview was that if I got the job I would be working out of the former HQ of the Cunard Shipping Line, who had taken over the grandiose South Western Hotel when they moved their UK base from Liverpool in 1965. This was the only BBC station complete with disused railway platforms, now in use for car parking, with overgrown track beds inhabited by rabbits and butterflies. At first sight it seemed oddly familiar. I realised that this was the very station my wife and I had passed through on the boat train to Southampton docks in 1967, to board SS Northern Star on our way to New Zealand. It now housed the BBC studio and offices, along with Radio Solent, but still retained the atmosphere of better days, with a splendid Victorian marble entrance hall, grand staircase and mahogany doors. It’s now been converted into luxury flats.

I was interviewed by a bunch of regional station managers including BBC South’s Laurie Mason, a former pioneering journalist credited with setting up the Points West programme while news editor for the old South and West region in the 1960s. He must have liked the cut of my jib because he offered me the job, much to my surprise and consternation.

On the plus side this move would mean living by the sea again, escaping a lifetime of home counties commuting and, for me, relative freedom from the oppressive TV Centre metropolitan regime. Against these advantages was the prospect of moving house for the seventh time in nine years, a change of schools for my daughters, saying goodbye to some good friends and neighbours, and…….working with journalists. We had only recently managed to buy our first house, a cottage in a village called East Peckham, down in mid Kent, where my son had recently been born. We loved it there, surrounded by hop gardens and apple orchards, so the prospect of yet another leap into the dark was not exactly welcome. But leap we did.

In the event, finding a new house was a nightmare, which meant my living away from home in Southampton digs Monday to Friday. This separation from my family lasted about eight months and did nobody any good at all. Finally I found a Victorian redbrick semi in Netley, famous for its connection with Florence Nightingale and its thirteenth century Abbey. The new house was right next to the railway station and within walking distance of Southampton Water via the former Royal Victoria military hospital grounds, or through the village to the local primary school and shops. I still had to commute, either by train or car (across the floating bridge from Woolston,) but the journey was short.

In the event, finding a new house was a nightmare, which meant my living away from home in Southampton digs Monday to Friday. This separation from my family lasted about eight months and did nobody any good at all. Finally I found a Victorian redbrick semi in Netley, famous for its connection with Florence Nightingale and its thirteenth century Abbey. The new house was right next to the railway station and within walking distance of Southampton Water via the former Royal Victoria military hospital grounds, or through the village to the local primary school and shops. I still had to commute, either by train or car (across the floating bridge from Woolston,) but the journey was short.

My job was to direct programmes transmitted by BBC South including the daily regional news magazine South Today and weekly regional features programmes known as Opt-outs, normally aired right after South Today. I shared an office with three other assistant producers, but was expected to work in the newsroom when allocated to South Today.

I write about working on South Today with some reluctance. I was keen to get out of London and this escape route, suggested by a very kind appointments officer, was not exactly plan A. The fault was all mine – I did not fit in to the newsroom operation, and over time I found the deadline-driven culture at once absurd and yet ever more stressful. I felt there was a middle class feel to the programme and most of the features content was often unimaginatively treated, sometimes based either on yesterday’s Southern Daily Echo or the news editor’s personal obsessions.

To make matters worse the newsroom felt to me like a cold-war zone – a den of petty rivalries and back-stabbing, probably due to the frustrations of competent desk journalists with thwarted ambitions, too often passed over career-wise. I was once told that I was not a proper director because I didn’t stand on a chair and shout at them. Well, you might have mentioned that definition at the appointments board Laurie.

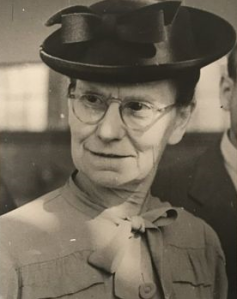

Don Osmond

What I was really after was working on the opt-outs, and this became very apparent to the journalists, including the programme producer, a former Southampton Echo journalist and gifted cartoonist, Don (not Donny!) Osmond, known to Echo readers as Oz.

“Don’s big break came when he was invited – as the Echo’s crime correspondent – to appear on a BBC show called Your Verdict, hosted by Ludovic Kennedy. The producer noticed him sketching away in his notebook and offered him the chance to contribute a topical cartoon after the news every night. After four years in this regular slot, Don took a job as producer for BBC’s news programme South Today in 1964 – and stayed for 20 years.” [Southern Daily Echo]

Don was one of the most likeable and liked colleagues I have ever worked with; I certainly liked him personally, but I think he knew himself that he was not well suited to his job, which he found very stressful. Me too Don.

In some ways Don could have been the model for the editor character in Drop the Dead Donkey, George Dent, (brilliantly played by Geoff Rawle,) much too nice for the job and bullied by all and sundry: “George is generally a moral man, who has a good sense of what a news company should really be doing and what stories are important, but he is frequently bullied by Gus (his boss) and distracted by his staff.” [Wikipedia]..

I am told that after he retired, Don went back to the Echo as a cartoonist and was much happier. Rest in Peace Don.

My worst moment:

Only rarely did I get a chance to get out of the newsroom to direct filming on location, with or without a reporter. One such commission concerned a millionaire who ran a country club somewhere in the New Forest. The story (or what passed for one,) was that every Thursday he would fly his light aircraft from Hurn airport to Cherbourg to buy fresh seafood to feature on the menu that evening. It seemed obvious to me that he was after a free commercial, but nobody in charge seemed to object. Well, ethics notwithstanding, he got his commercial. I and what was laughingly known as the film crew duly flew over in another plane, at the millionaire’s expense, and we met up with him and his minder, and our reporter, at Cherbourg airport.

The filming was a bad joke. The millionaire, a former stock car racing tycoon, blundered his way round the indoor market insulting all and sundry, shouting in Cockney and doing a lot of pointing. Staff news cameraman Ron (who hated the idea of being told what to do by a jumped up graduate pretending to be a film director – or, I suspect, by anybody,) barged his way round with him and his minder, blazing away with his 16mm film camera without much thought for the needs of editing, which he thought were an artsy-fartsy myth created by film editors to make his job harder.

The filming was a bad joke. The millionaire, a former stock car racing tycoon, blundered his way round the indoor market insulting all and sundry, shouting in Cockney and doing a lot of pointing. Staff news cameraman Ron (who hated the idea of being told what to do by a jumped up graduate pretending to be a film director – or, I suspect, by anybody,) barged his way round with him and his minder, blazing away with his 16mm film camera without much thought for the needs of editing, which he thought were an artsy-fartsy myth created by film editors to make his job harder.

After the shoot, the real purpose for the day became evident as we were all driven off to a rural Normandy restaurant for a slap-up haute cuisine lunch. The resulting feature was just about transmittable, but not on the day, as planned, due to the ridiculous amount of time taken witnessing our portly millionaire stuff himself before staggering back to the airport and starting on the repair work needed in the cutting room. To my surprise quite a lot of the market footage was visually attractive, so I decided to use the best of it to create two montage sequences cut to music, mainly to pad out the story, which really ought to have been a one minute soft news item, or better still, dropped altogether. Not exactly an original ploy on my part.

But during the editing, I made the mistake of letting my anger about the experience override my better judgement. I decided to cut the montages to two songs whose lyrics would reflect badly on our millionaire. The two songs were “Poor people”, by Alan Price and John Lennon’s “Baby you’re a rich man now”. This egregious departure from Auntie’s golden rule of impartiality ought at least to have had a disciplinary outcome, or even the sack, for me, bit it didn’t, which in itself is a criticism of BBC South’s governance at the time. I don’t recall anyone with editorial control viewing the edited story before it went to air. Perhaps they did and were out to teach me a lesson.

I could not have got it more wrong. As I was sitting in the gallery directing the programme, as I rather expected, a phone rang, asking me to report to the newsroom after the show to deal with numerous calls being made by viewers. This it I thought, the end of my illustrious BBC career, but no, all the calls were from delighted viewers wanting contact details so they could book a meal at this wonderful country club. Two lessons – never let your personal feelings cloud editorial judgement and never presume to know or understand your audience.

I never found out what the millionaire thought of his free commercial on non-commercial television, but I was kept awake by the thought that his minder (a rather nice bloke actually,) would be after me up a dark alley. (I did have reason to believe he was armed during the filming……..)

Over time, things got better, partly due to several colleagues in and around the newsroom who must have noticed what I was achieving as I worked more and more on opt outs. Too many to name, but there are three whom I would like to mention:

Bruce Parker:

Bruce Parker:

An abiding memory is working with our long-standing and long-suffering anchor man Bruce Parker, later to be better known as presenter of the Antiques Road Show, and awarded an MBE last year. At first he came across as abrasive, unforgiving and arrogant. He certainly gave me a hard time, but even then I understood that any mistakes I made in the gallery had to be dealt with on air by the presenter. I had been warned that he had a track record of taking no prisoners, especially directors, so I just kept out of his way other than during transmission. I did however respect his professionalism as a presenter and reporter, and I still do.

But then things changed, once I managed to worm my way out of South Today and move on to the opt-outs almost full time. Bruce and I started to talk. He was a great admirer of “Hey Look That’s Me”, the ground-breaking children’s opt-out programme I directed for a few years, and later, “Don’t Fence Me In”, my own environmental magazine programme which I produced and sometimes directed.

Out of the blue one day Bruce wandered into the opt out office and suggested an idea for “Don’t Fence Me In”, which I thought was as a good one. He had come across a landscape ecologist called David Streeter whom Bruce thought was a natural on camera, and together they had developed a simple format where the two of them would go on a country walk chatting about the flora and fauna they came across along the way. A simple format, bang on our agenda. We shot two or three walks I think, quite near to Bruce’s cottage near Winchester. Really these stories made themselves, as these two consummate professionals, working with a competent (and occasionally inspired,) director and an excellent camera crew, came together and produced well crafted features for a known audience. No scripts, just knowledge of the subject matter, making it up as we went along.

Jenni Murray

Jenni worked a reporter and presenter of South Today from 1978 to 1983, then left to work on Newsnight and the Today programme, before taking over from Sue MacGregor on Woman’s Hour. I was still working mainly on South Today when Jenni started at South Western House. Having come from Radio Bristol, she was new to television, but she took to it very quickly, and we were on good terms most of the time.

Jenni worked a reporter and presenter of South Today from 1978 to 1983, then left to work on Newsnight and the Today programme, before taking over from Sue MacGregor on Woman’s Hour. I was still working mainly on South Today when Jenni started at South Western House. Having come from Radio Bristol, she was new to television, but she took to it very quickly, and we were on good terms most of the time.

Later on we worked together on some stories which she felt needed some directorial input on location, at her request. The deal was clear, Jenni would do the research, conduct interviews, pieces to camera and voice-overs, leaving everything else to me and the crew. This was a delight, I think for both of us, and might have led to a longer professional working relationship in time, had we not both left BBC South at around the same time.

I also worked with Jenni on a programme about town twinning which I produced and directed. She presented the programme and interviewed a very old lady who had been one of the early pioneers of twinning after the war, when she was the Mayor of Reading. Phoebe Cusden had responded to stories told by returning British soldiers about the desperate state of bombed out children in Düsseldorf in 1947, and resolved to set up a scheme to adopt some of them in Reading. I recall Jenni and I having doubts about the wisdom of interviewing a lady in her nineties, but as soon as the camera rolled my fears evaporated:

I also worked with Jenni on a programme about town twinning which I produced and directed. She presented the programme and interviewed a very old lady who had been one of the early pioneers of twinning after the war, when she was the Mayor of Reading. Phoebe Cusden had responded to stories told by returning British soldiers about the desperate state of bombed out children in Düsseldorf in 1947, and resolved to set up a scheme to adopt some of them in Reading. I recall Jenni and I having doubts about the wisdom of interviewing a lady in her nineties, but as soon as the camera rolled my fears evaporated:

I was surprised and delighted to find recently that this moving and inspiring story has been rediscovered by a BBC Online journalist, featuring the memories of one of the girls on Phoebe’s scheme who gained a German sister in this, one of the earliest post war anglo-german twinning schemes.

This is an extract from a letter from the Chairman of the Reading Düsseldorf Association, dated June 15 1981. (Click to enlarge)

This is an extract from a letter from the Chairman of the Reading Düsseldorf Association, dated June 15 1981. (Click to enlarge)

Jenni is now Dame Jenni, and has recently celebrated 30 years on Woman’s Hour.

🎉 🌟 Congratulations to our very own Jenni Murray! She’s been presenting @BBCWomansHour for 30 years and has met a LOT of amazing people. pic.twitter.com/UC0Wn2p9Ao

— BBC Radio 4 (@BBCRadio4) September 14, 2017

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Jenni’s Profile (BBC)

Enid Hewitt

I’m not sure what Enid’s official job title was, but it didn’t take me long to work out that whatever it was, she ran the show. She was in daily charge of newsroom admin, the rock around which we all swam. She kept the all important diary, chivvied up the journos and reporters, made sure scripts were fed to the typists, took minutes of meetings and probably a lot more I didn’t know about or can’t remember. She saw us come and go – journalists, producers, news editors, and treated us all as her second family. I didn’t know it then, but the knowledge of newsroom organisation I gained from her was to be very useful to me years later when I was commissioned as a consultant for the Swedish speaking news service at YLE in Helsinki. Enid died recently, and I regret not being able to attend her funeral. RIP Enid.

To be continued

Sources

My memory

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-hampshire-38468158

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-berkshire-40160310

http://www.dailyecho.co.uk/news/5634323.TRIBUTES_PAID_AFTER_ECHO_CARTOONIST_DIES_AT_69/?ref=arc

Pingback: My window faces the south Part 2: John Fowles | Peter Dewrance

Pingback: New Zealand days – part 1 | Peter Dewrance

Pingback: My window faces the south: Netley days | Peter Dewrance

Pingback: Canteen Days | Peter Dewrance